With the many expected setbacks and delays, we’ve been lucky enough to have a science plan that includes backups. Those backup sites have allowed us the chance to practice the critical elements of glacial geology field work. Everyone now knows how to collect a rock. Everyone now knows how easy it is to rush or be distracted by shiny things. We’ll still do it…but we know the impact.

Photo credit: Bia Bouchinas

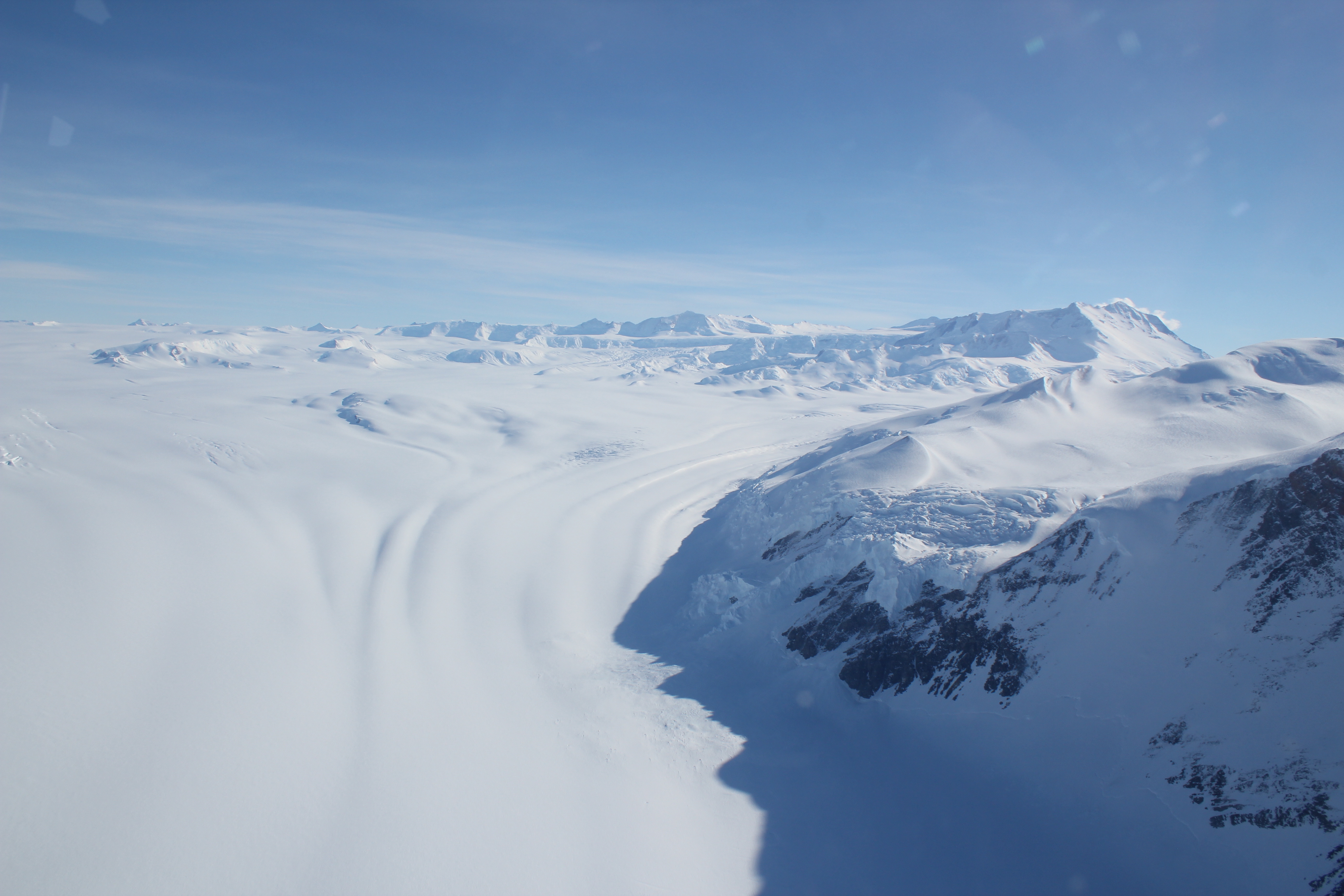

Our overarching goal, over multiple field seasons, is to understand the glacial history of one of the largest glacial systems on the planet. The Byrd and Mulock Glaciers drain a combined 1.25 million square kilometers of the massive East Antarctic Ice Sheet which is effectively the planets largest water tower. That makes these two glaciers area roughly the size of Peru or South Africa…or twice the area of Texas. And in places, this ice is over 4 km thick. A lot of ice, eh? That represents ~20% of the ice to the world’s largest floating chunk of ice, the Ross Ice Shelf. It’s easy, to us anyways, to see how understanding the history of such a significant portion of ice can help unravel Antarctica’s past sea level contribution and how it helps forecast Antarctica’s future.

On to the rocks! Our first field shakedown involved a day trip to Minna Bluff, just a mere 80 kilometers from Scott Base. At this site, and if you take yourself back 20,000 years ago, you may have seen a fast-flowing ice stream emanating from both the Byrd and Mulock Glaciers. This ice stream would have plucked rocks from it’s bed and transported them along its path. In some cases, these rocks would make it all the way to the continental shelf and quite possibly calve off into icebergs as they float around the continent, melting out little rock droppings to the sea floor as they encounter warmer waters.

Photo credit: Bia Bouchinas

But back here at Minna Bluff, the overriding ice would eventually start to thin as the world warmed up, dropping foreign rocks onto the ~9-million-year-old volcanic landscape. These foreign rocks, shaped by ages of glacial action, have no business being here and stick out like a sore thumb. The plethora of white granite and gneisses tell us that glaciers have been here and if we are lucky and a little bit skilled, we’ll be able to extract their history of ice sheet change.

You may be wondering how we choose our sites and what makes a good site. In most cases, we like being near fast flowing, dynamic ice with adjacent rock that emerges from the modern ice level. Then we want to know if glacial erratics are present…in the case of Minna Bluff, we knew they existed because Anne Wright previously collected and donated them to the Polar Rock Repository! This site proved to be a successful site for sampling and we collected a suite of rocks up to 700 meters. A great day out and a first for our two students!

Photo credit: Bia Bouchinas

Further upstream along the Mulock Glacier, at Mt. Marvel, we found an entirely different landscape formed by erosion and breakup of Gondwana, the supercontinent that once dominated Earth’s terrestrial environment. Here, we found a beautiful stack of Permian sandstones, called the Beacon Supergroup. These sandstones show evidence of great rivers and fossils that lived in and around those rivers. And like another sore thumb, the Jurassic volcanic deposit of the Ferrar Dolerite, provides a stark contrast both in rock type and in time. This volcanic deposit records the breakup of the supercontinent and interrupts the order of time in this stack of rocks. All very interesting geologic wonders but we are here to tell the history of ice…

Photo credit: Bia Bouchinas

Here at Mt. Marvel, we already knew that glacial action was recorded here. Stunning glacial striations, subtle scratch marks made by rock laden ice, and perched glacial erratics tell us we have a good chance of extracting a glacial history here. Returning to this site after nearly being blown off of it in 2019 would special if not nerve-racking. Would we be blown off of it again? Would we find glacial deposits at higher elevations, and thus older, evidence of glacial history? Only one way to find out.

Photo credit: Bia Bouchinas

To our surprise, and only after 1 hour on site, the wind turned off like a light switch. After ascending to the highest point possible, we did see evidence of glacial scuff marks and our precious little glacial droppings. With a stunning bluebird day, close helicopter support and a keen eye, we finished the job started in 2019. We simply cannot wait to finish this story and tell the first long-term glacial history of the mighty Mulock Glacier.

Enjoy this little video compilation of the day visits. We hope you come back to hear more about our field season…and here’s hoping we make it to camp along the Byrd Glacier. Any questions, fire away. Subscribe for more updates.